Microfinance: creativity against poverty

Special Report: FT Wealth, by: Gill Plimmer Date: 23 October 2016

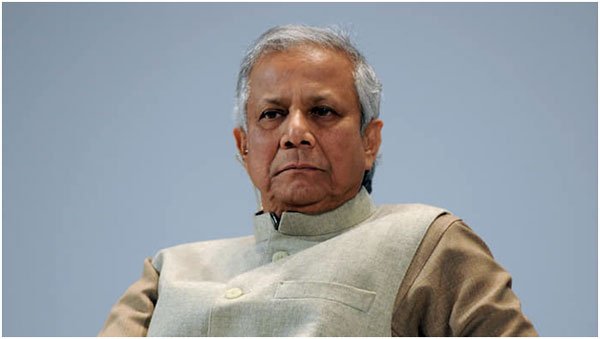

Banker Muhammad Yunus talks about Grameen Bank and his lending initiative Women in Mumbai, India, gathered to hear about the benefits of microfinance © Eyevine

Muhammad Yunus is a banker who talks as if he’s an artist. The Nobel Peace Prize-winning founder of the microfinance movement that provides loans to people excluded from the financial system says he sees entrepreneurship as a creative endeavour.

“All human beings are packed with unlimited creative capacity. A job is the end of creative capacity. You take orders from your tiny boss who works above you and you fashion your life according to the desires of your tiny boss and you forget all about your creative power,” he says. “This is a shame.”

In the three decades since Yunus set up Grameen Bank in his home town of Dhaka, Bangladesh, the 76-year-old has won numerous accolades for his work and helped legions of hairdressers, basket makers and door-to-door fruit sellers to establish their businesses and escape poverty.

In August, he carried the Olympic torch in Rio de Janeiro. His model of providing small loans to people, mostly women, has been embraced across the world, from India to China, from Glasgow to New York, and has won celebrity supporters such as Hillary Clinton, the Democratic nominee for US president. He has even guest-starred in television cartoon show The Simpsons.

Yunus was in London a few months ago to promote his business to leading philanthropists. But the city, despite being a hub for international finance, has remained stubbornly resistant to his microfinance movement — even though he says he has met more government officials and finance executives in the UK than in other, more receptive countries, such as France and Germany.

“I would say I’ve had more support from other countries,” he says. “Support in terms of helping us to open the door to other people, not that they give money to us. That’s not what we are looking for. [London] is the financial capital of the world; it should also be the microfinance capital of the world.”

The lending initiative launched in Glasgow in 2013, supported by Tesco Bank, the supermarket chain’s finance arm, which invested up to £500,000 in loan capital. But despite the prevalence of loan sharks in the UK, which highlights the need for ethically based small loans, he says the rest of the country has failed to embrace the microfinance movement.

The UK’s dearth of enthusiasm puzzles Yunus, though he refuses to speculate why. But it is no surprise that having rejected charity as the best means of dragging people out of poverty, he is also critical of welfare, other than in crises. He views welfare as a deterrent to work, but such beliefs mean not everyone sees Yunus as a champion of the poor.

Over the past 33 years, Grameen Bank has lent to 8.5m people in Bangladesh alone, but there have been concerns that the rates charged on the loans — of up to 20 per cent — are still high, even if they are far lower than local interest rates in developing countries or the 300 per cent or more that loan sharks or payday lenders might charge.

While Yunus describes the bank as a charity, it always recoups its investments and the business must cover its full costs.

Sheikh Hasina Wajed, prime minister of Bangladesh, has said Yunus is “sucking money from the poor”.

In India six years ago, a spate of suicides by harassed microfinance borrowers also raised concerns about the movement. Some had taken out loans with a company set up by an acolyte of Yunus, though none were known to have borrowed from Yunus’s enterprise itself. None of the accusations has stuck and Yunus himself denies all the allegation. He continues to travel frenetically — London this week, home to Dhaka the next, Rome the week after — promoting social enterprise and garnering supporters and borrowers along the way.

None of the accusations has stuck and Yunus himself denies all the allegation. He continues to travel frenetically — London this week, home to Dhaka the next, Rome the week after — promoting social enterprise and garnering supporters and borrowers along the way.

“If some guy in Manila, in some microprogramme, charges exorbitant interest rates and somebody committed suicide, you can’t blame me for this. I cannot have caused that,” he says, conceding that some organisations are abusing the microcredit system for profit.

“In Grameen Bank, our basic rule is that we won’t punish anybody for anything. So we work with them; help them to restore themselves and if the borrower dies nothing has to be repaid.”

Still, even Yunus acknowledges that he is a beneficiary of a flawed financial system that rewards money with more money. “I’m not a bad guy; I’m a good guy.,” he says. “I say all the good things and I make beautiful speeches and really I genuinely believe that. But I put the money in [through investment trusts] and the money is working.

“The system always puts money at my door. And I can’t help it. I keep on accumulating. I sleep at night and I wake up in the morning and my wealth has doubled. I didn’t do anything, I just slept. We have to undo the system that automatically gives me money without any contribution from my side. The banking and financial system is “wrong”, he says. “Their basic policy is the more you have, the more I give you. So wealth concentration takes place.”

The banking and financial system is “wrong”, he says. “Their basic policy is the more you have, the more I give you. So wealth concentration takes place.”

Indeed, 40 years after Yunus, then a university lecturer, was inspired to take action by what he saw in the slums of Dhaka, he is increasingly troubled by the increasing inequality worldwide. Citing a report that claims 99 per cent of the world’s population own only about 50 per cent of the wealth, he says: “The growing inequality is a time bomb. Nobody’s paying attention to it. It could be a revolution, decivilisation — all kinds of things are possible.”

Addressing the financial elite in London, Yunus promoted the idea that the wealthy should accumulate first, then share their riches for the common good. “So, for the first phase, up to about 50 [years old], people devote themselves to making money, and for the second phase, they devote themselves to giving it away,” he says.

Ultimately, though, Yunus believes all of us, wealthy or poor, should explore our creative powers and become entrepreneurs.

“When 7bn people become entrepreneurs, it will not be easy to concentrate all the wealth in a few hands,” he says. “You have to open that door of entrepreneurship.”

Source: https://www.ft.com/content/